The Chicago Imagists are having a moment. Again.

Since the independent-minded, often irreverent artists jumped into view in Chicago in 1966 with the first Hairy Who show, the group has had its down moments, including a backlash against its local pervasiveness in the 1980s.

“There was a time when it seemed like: Oh, these guys are going to disappear maybe,” said Richard Hull, a Chicago artist who began showing in the same gallery with the Imagists in 1979 and has known many of them. “But that was really brief, because what happened was that other parts of the world became enamored or influenced by what was going on here.”

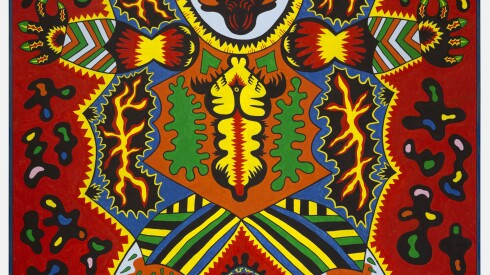

Roger Brown’s “Hancock Building.” In December 2024, the Kohler Foundation announced the purchase of the Roger Brown Study Collection. It subsequently donated the group of about 3,000 artworks and other objects collected by one of the most famous Imagists to the Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wis.

Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Whether measured by the sale prices of the Imagists’ work or their inclusion in national and international art shows, their overall trajectory is clear. Up. Way up. Indeed, as Chicago’s best-known art movement approaches its 60th anniversary, it has never enjoyed more success. The evidence is everywhere:

- Six of the Imagists are featured in “Sixties Surreal,” a reappraisal of American art from 1958 to 1972 that runs through Jan. 19 at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City.

- Gladys Nilsson, one of the six members of Hairy Who, the most famous subset of the Imagists, will be showcased July 19-Nov. 29, 2026, at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, Calif., in what is billed as her first large-scale retrospective.

- In December 2024, the Kohler Foundation announced the purchase of the Roger Brown Study Collection. It subsequently donated the group of about 3,000 artworks and other objects collected by one of the most famous Imagists to the Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wis.

- GRAY, a prestigious gallery with branches in Chicago and New York, began handling the Brown estate in November, showing his work earlier in December at the international art fair, Art Basel Miami Beach, and planning a solo exhibition for the spring.

- The catalog for “3-D Doings: The Imagist Object in Chicago Art 1964-1980,” a show held in 2018-19 at the Tang Museum in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., was belatedly published in September, bringing renewed attention to the show and the Imagists.

- “Christina Ramberg: A Retrospective,” organized by the Art Institute of Chicago, ended its tour in June at the Philadelphia Art Museum after a previous stop at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles.

“They’ve been extremely relevant to visual culture for a very long time,” Dan Nadel, a co-curator of “Sixties Surreal,” said of the Imagists. “It’s just that institutional appreciation took a little longer to catch up, but it is happening.”

It is difficult to pin down the exact membership of the Imagists, a term coined by the art critic Franz Schulze, because it was not so much a movement as a kind of grouping of Chicago artists with similar interests and styles. Many of the artists who are so designated are not fond of the appellation, including one of the best known, Jim Nutt. “We just got stuck with it,” he said.

The main contingent of Imagists, the 14 featured in a 2014 documentary on the group, “Hairy Who & The Chicago Imagists,” directed by Leslie Buchbinder, were School of the Art Institute of Chicago alumni. They emerged in 1966-73 during a series of exhibitions at the Hyde Park Art Center (each with deliberately nonsensical names, with Hairy Who being by far the most famous) organized by the prescient curator, Don Baum.

Among the best known of those 14 are Brown, Nilsson, Nutt, Ramberg, Ed Paschke, Karl Wirsum and Ray Yoshida. Others who are often considered Imagists or at least mentioned alongside them include Miyoko Ito, Robert Lostetter and Richard Wetzel.

“All of us have had varying success over the years,” Nutt said. “Sometimes more, sometimes less. And we’ve gone through so many art-world disruptions, but we somehow got slightly ahead of it, always managed to make just enough money to stay ahead of struggling, and we just keep working.”

At a time when the art world was dominated by minimalism and pop art, the Imagists developed an often rambunctious, some sometimes ribald figurative style that drew on sources ranging from the vernacular world of the old Maxwell Street Market to Oceanic and other non-Western art at the Field Museum. At the same time, these artists weren’t afraid to break art-world “rules.”

“You were allowed to do all kinds of things to your work,” Hull said. “You could put hair on it. You could paint on Plexiglas. You could paint on window shades. You could make quilts. You could make toys. They expanded the ways in which you might make art.”

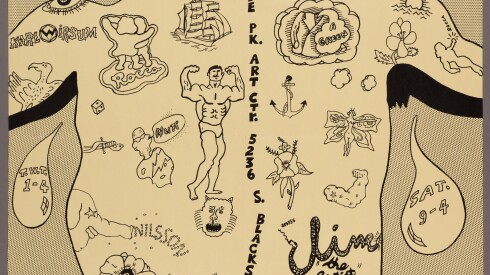

The main contingent of Imagists were School of the Art Institute of Chicago alumni. They emerged in 1966-73 during a series of exhibitions at the Hyde Park Art Center (each with deliberately nonsensical names, with Hairy Who being by far the most famous) organized by curator Don Baum.

Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

The immediate success that the Imagists garnered from the Hyde Park shows gained them national attention, especially the six Hairy Who artists who had exhibitions in San Francisco, New York and Washington, D.C., before they disbanded in 1969.

But in part because of the dominance of the New York art scene, with formalist art critics like Clement Greenberg wielding enormous power, and biases about so-called regional art, the Imagists have faced headwinds despite the considerable recognition they have achieved.

Karen Lennox, a longtime Chicago art dealer who worked from 1972-81 at the influential Phyllis Kind Gallery, which represented the bulk of the Imagists, believes the escalating values of their art have still not kept up with the rest of the market. “They’re completely, totally underpriced,” she said.

On the institutional front, according to Nadel, only now are museums finally catching up to the importance and contributions of these artists, who have influenced everyone from Gary Panter, one of the core designers for “Pee-wee’s Playhouse” to artists like Nicole Eisenman, Kerry James Marshall and Amy Sillman.

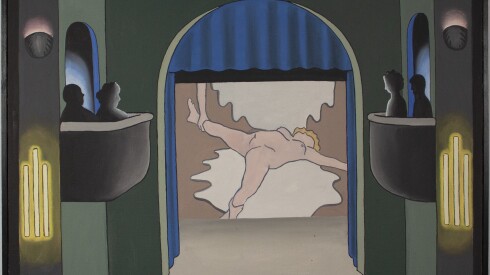

Christina Ramberg’s “Bagged.” The artist was the focus of a 2024 retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago. The survey contained more than 100 paintings, quilts, drawings and other objects — about two-thirds of all the work she created in a life that was tragically shortened by an 1989 diagnosis of Pick’s disease or frontotemporal dementia. The illness curtailed her artistic output and ultimately led to her death in 1995 at age 49.

Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

That’s where a show like “Sixties Surreal” comes in. It offers a total rethinking of the period running from 1958 through 1972 and features 100 artists who deviated from the artistic strictures of the time and took off in their own experimental directions.

“It’s important to say at the top: This is not a show of surrealism,” Nadel said. “It’s a catchy title for a show that is about emerging artists in the 1960s who were given permission by surrealism to take on all kinds of different subject matter and different kinds of visual languages.”

He called the Imagists “one of the pillars” of the exhibition from its earliest stages. “It was a given that they would be in it,” Nadel said. “Very few other artists represent this [outlier] idea as well as they do.”

Francesca Wilmott, curator of the Crocker Art Museum, believes that the single biggest boost to the standing of the Imagists came in 2018 when the Art Institute presented “Hairy Who? 1966-69,” a major retrospective of the group.

“Their [accompanying] book is continuing to circulate and I see it in bookstores all over the world,” Wilmott said. “That exhibition grounded the Imagists and the Hairy Who in scholarship that had been sorely lacking on these artists.”

She hopes Nilsson’s retrospective at the Crocker will fill another scholarly void. Titled “Gleefully Askew,” it will include 100 works and cover her entire 60-year-plus career. The show is set to travel in 2027 to the Madison (Wis.) Museum Contemporary Art, which has one of the largest public collections of Imagist art anywhere and is opening a dedicated Imagist exhibition space in late 2028.

Nilsson and her husband, Nutt, lived in Sacramento in 1968-76, when he held a full-time post at Sacramento State University, and she taught part time. Wilmott called this a “formative moment” in her career, when she was able to break out and assert her artistic individuality.

“I see Gladys as a major American painter of her time,” the curator said. “She has been exhibiting nationally and internationally throughout her career, but she hasn’t really gotten the academic focus that her work deserves. We’re hoping to change that with this retrospective.”

As the Imagists move past this latest anniversary, Hull is confident they will only continue to solidify their place in American art history.

“I think the work is so strong and so particular that it has to survive,” he said. “The artists were just so good.”