When Drs. David Blatt and David Moore founded the AIDS ward at Illinois Masonic Hospital in Lake View in 1985, they figured they were all but guaranteed to end up in one of the unit’s beds, face-to-face with their own diagnosis and anticipating their own death.

“For three years, I assumed everything I saw was my future,” said Moore, recalling the gruesome lesions, fevers and heart failure that often preceded death.

The ward, called Unit 371, was the backdrop to many patients’ worst days. Blatt and Moore, who today are married, described the unit as a place of stubborn resilience, prevailing love and strong community in the face of insurmountable grief.

It was there they kissed the foreheads of patients after giving bad news, comforted grieving family and friends, celebrated their wedding with a cake homemade by one of the unit’s nurses, pushed beds together so infected lovers could be closer and sobbed behind closed doors in their offices when it all became too much.

After witnessing tragedy after tragedy as the disease ravaged Chicago’s gay community in nearby Boystown, they are now living what Blatt calls a “dream come true” — a world where an AIDS diagnosis is no longer a death sentence.

But his hopes for a future where AIDS is eradicated are now threatened by President Donald Trump.

It took more than a decade of medical research and activist pressure before the tide of suffering caused by the crisis began to recede, slowly ushering in a new era of improving treatments and longer lives for patients with the virus.

But in recent months, the Trump administration has targeted access to health care and the LGBTQ+ community and cut a $258 million program seeking to develop an HIV vaccine.

Activists have sounded the alarm, warning the cuts roll back decades of progress made in health care and LGBTQ+ rights.

Blatt and Moore know well what going backward could look like. They’re haunted by memories of the days when AIDS controlled life on Unit 371.

“It’s about what they consider to be a marginalized community,” Moore said. “We’re easy fodder for whatever political clout they think they can get out of treating this marginalized population poorly.”

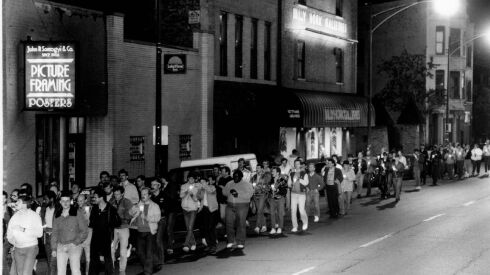

‘Ground zero’ for AIDS in Chicago

In 1985, Dr. Merle Sande, then-chief of the AIDS research task force in California, told the Chicago Tribune: ”We are clearly in the midst of a major medical catastrophe, the potential impact of which is now only beginning to be realized.

The future looked bleak. Researchers at the time had seen cases double every six to 12 months since 1980.

By 1995, AIDS had transformed from a poorly understood yet heavily stigmatized “gay cancer” to a disease that could be somewhat managed. To get to even that point, activists and doctors fought hard. But nationally, in Illinois and in Chicago, the virus’ mortality was still peaking.

That year, Illinois recorded its highest mortality with 1,427 people dying of AIDS and related complications, including 1,274 in Chicago, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Chicago Department of Public Health.

Unit 371 was “ground zero” for the AIDS crisis in Chicago by then, doctors who spoke to the Sun-Times recalled. It served as a “hospice” to many who weren’t expected to recover — and in the early days of the epidemic, that was nearly every patient.

“I remember sitting in my office many times closing the door and just sobbing uncontrollably because that grief and disbelief had to go somewhere,” Moore said. “To this day, there’s certain songs I hear, or memories I have, or names I hear that will cause me to just begin to cry.”

Prominent AIDS activist and political cartoonist Daniel Sotomayor died there in 1992. In the years leading up to his death, Sotomayor and his best friend and fellow activist Lori Cannon, spent their time attending funerals and memorials, stitching the AIDS memorial quilt and visiting friends on Unit 371. Cannon spoke with the Sun-Times about Unit 371 in July, about a month before her death of heart failure at age 74.

“I never thought, ‘Oh, we’re going to lose him,’” Cannon said. “We lived our lives, period. And each day was a gift because he was managing, and he looked beautiful, and chemo had not taken away his gorgeous head of hair.”

A spokesperson for Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center wouldn’t disclose how many patients died of AIDS at the hospital during the unit’s 15-year lifespan, but said “thousands” were treated there.

Hospital staff became surrogate family members to patients who had been rejected by their families, said MK Czerwiec, a nurse who worked on the unit and wrote the book “Taking Turns: Stories from HIV/AIDS Care Unit 371.”

“The staff on the unit stepped in serving as family members as much as possible,” Czerwiec said. “So there was more than just passing meds and procedures.”

And the unit became as much a social hub as a treatment facility.

“It was like going to a gay bar, but out of beer,” said Raju George, a nurse in the emergency department who is gay and has worked at Masonic since 1995.

Unit 371 was the first of its kind in Chicago and inspired similar wards nationwide and in the city, like the 11th floor at Lake View’s St. Joseph Hospital. It paved the way for doctors to shift toward a now-standard “compassionate care” model of treatment, said Dr. Renslow Sherer, who worked at Cook County Hospital during the crisis and co-founded the AIDS Foundation of Chicago.

“We wanted to be sure that we had a dedicated unit where every nurse was trained and comfortable and could provide ultimate care so that no patient ever felt stigmatized or different,” Moore said.

Greg Harris was diagnosed with HIV in 1988 and AIDS in 1990. He wasn’t given a high chance of survival, and he was admitted to Unit 371 for a week with digestive failure. He survived.

At the time, his priority was caring for friends whose infections were more severe or who were facing discrimination based on their sexuality or AIDS status, he said.

“You were trying to deal with the most intensive need each day, and that was one way to avoid confronting what may happen to you in six months or whatever,” Harris said.

Blatt and Moore saw many friends come through their hospital, including the very first case they saw in 1982. Many never went home.

When asked to speak about any specific patients he remembered, Moore declined.

“It’s so many, you couldn’t possibly,” he said. “Besides, I’ll start crying and not be able to recover.”

‘We’ve been set back several years’

The AIDS epidemic began to take a turn in 1996. The federal government approved at-home testing, viral load testing and urine testing. An International AIDS Vaccine Initiative was also formed to expedite a vaccine.

Nationwide, the number of new cases dropped for the first time since the beginning of the crisis and AIDS was no longer the leading cause of death for Americans ages 25-44, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Between 1995 and 1997, the deaths per 100,000 population in Illinois had plummeted from 11.9 to 4.2.

By 1997, Unit 371 had reduced to half its 24-bed capacity as hospitalizations from AIDS fell and the hospital shifted to more outpatient care.

And the mortality rate for HIV/AIDS in the U.S. has fallen in the decades since, helped along by advances in pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, a medication regimen that greatly reduces HIV risk. According to the CDC, deaths per 100,000 population in Illinois fell to 0.8 in 2022.

The situation would sound fantastical to Blatt’s younger self.

“When everybody’s dying, you have this fantasy that things would stabilize, that people would quit dying, that people would actually be okay,” Blatt said. “And it actually happened.”

Harris said his intimate experience with the AIDS epidemic shaped how he governed as the majority leader in the Illinois House of Representatives at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. The national and local responses to the AIDS epidemic were widely criticized during the crisis and in the years since, particularly the inaction of former President Ronald Reagan.

“I had an opportunity to play a role in making sure … that we did not repeat the same ignorant political mistakes of the past,” Harris said.

Ald. Tom Tunney (44th) and U.S. Rep. Mike Quigley pat Illinois House Majority Leader Greg Harris on the back after Harris shared his experience being openly gay and HIV-positive during the AIDS Garden’s groundbreaking ceremony on the lakefront near Belmont Harbor where Belmont Rocks used to be, Wednesday morning, June 2, 2021. Chicago’s LGBT community used to gather at Belmont Rocks in the 1960s and 1990s.

Pat Nabong/Sun-Times/Pat Nabong/Sun-Times

Doctors who treated AIDS now see the White House working to unravel that progress at a time when the virus still affects millions globally.

The Trump administration has targeted access to health care and the LGBTQ+ community in his first months in office, ending the program seeking to develop an HIV vaccine, and slashing the U.S. Agency for International Development, which is credited for humanitarian efforts over 60 years. Historically, vaccines have been the most effective tool to mitigate, and even eradicate, contagious diseases from viruses. An HIV vaccine could save millions of lives, and even a partially effective vaccine can lower the transmission rate substantially, according to HIV.gov, the federal government’s HIV resources hub.

The National Institutes of Health have also cut grants related to PrEP, and The New York Times reports the State Department is working on scrapping the program for fighting AIDS in developing nations.

“Viruses we can understand, but the human beings then make it all the much more worse,” Moore said. “It’s just incomprehensible.”

Some “critical” HIV/AIDS programs will be continued under the Administration for a Healthy America, part of the Trump administration’s restructuring of several federal government agencies, including the Department of Health and Human Services.

“This area is a high priority for both NIH and HHS,” the NIH said in a statement. “Ongoing investments reflect our dedication to addressing both urgent and long-term health challenges.”

But for Sherer, the last several months have been a dramatic setback in efforts to eradicate AIDS.

“If you’re looking for current lessons, that’s [to] stay resilient and active, because we’re not only not done, but we’ve been set back several years,” he said.