EDITOR’S NOTE — This story includes discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, the national suicide and crisis lifeline in the U.S. is available by calling or texting 988. There is also an online chat at 988lifeline.org.

Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood is known for its pristine foliage and manicured landscape, not to mention its scenic residential areas.

Longtime Chicago tour guide Tony Szabelski describes it as “one of the most upscale neighborhoods in Chicago to live in.” He often leads city tours through the neighborhood and said it’s a safe place to be, even at night.

But behind the bubbly chatter of the free Lincoln Park Zoo, the buzz of cyclists on the park’s many paths and the cheers from its sports fields is a hidden, macabre history.

More than 100 years ago, dozens of people met their deaths near a sightseeing attraction that was notoriously known as the “Suicide Bridge.”

“Louis Rockne’s fatal jump from the High Bridge” read a headline from the Chicago Daily Tribune in 1898. By summer of that year, the newspaper reported that nearly 20 people had died by jumping off of the bridge.

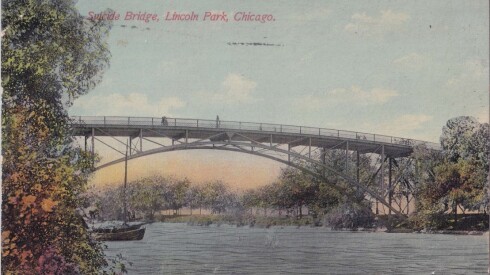

Officially called High Bridge, it was constructed for typical public activity: water sports, picnicking and pedestrian access to Lake Michigan. This was during the turn of the century, as rapid economic growth widened the gap between the rich and poor. Some people had little relief from economic and social hardships. Of all the areas across the city, it was the High Bridge where dozens of people came to end their lives. Experts today say it all could have been avoided.

A bridge with a view

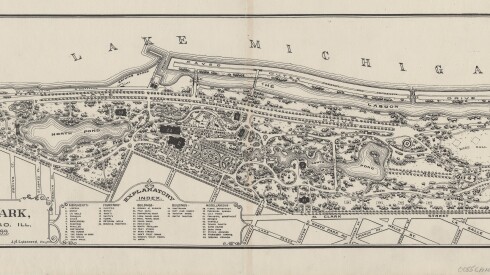

The High Bridge was built in the early 1890s, around the time of the World’s Columbian Exposition. It provided pedestrian access to Lake Michigan between Fullerton and North avenues, which are a mile apart. Old maps show the bridge straddled the lagoon in Lincoln Park, south of Fullerton and east of what is now the Lincoln Park Zoo.

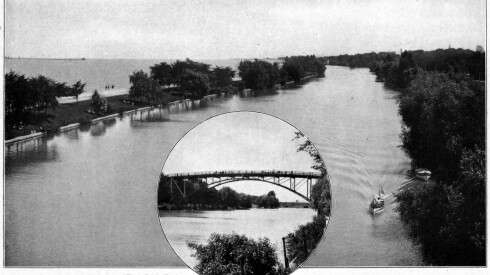

Before skyscrapers were built downtown, High Bridge was taller than any structure around the park, standing an estimated four stories high. Visitors could see all the way to Jackson Park from its peak.

People came from all over the city to admire the view, ice skate during the winter and picnic in the summer. According to Paul Durica, director of exhibitions at the Chicago History Museum, boat races and swimming competitions were staged under and around the bridge. Spectators used it as a prime observation point.

The Charles Tyson Yerkes rowing competition was held at the lagoon in 1895. Duke Kahanamoku, known today as the father of modern surfing, and fellow Hawaiian swimmers and divers put on a show at the bridge in 1918.

Despite the fanfare the High Bridge attracted, within a few years, it developed a more morbid reputation.

The Bridge of Sighs

According to the Herald News, between 1899 and 1909, more than 25 people “leaped to their death” off the bridge. Other news reports mention people who died by taking poison on or near the bridge.

It soon became known as the “Bridge of Sighs” or “Suicide Bridge,” with newspapers printing the moniker as early as 1898.

“It’s not just people living within walking distance of Lincoln Park,” Durica said. “That’s what I find fascinating, is it was such a deliberate choice and act you made, almost like a ritual in a way. This was the place where you came, when you got to a point where seemingly no other decision existed.”

But people didn’t just come to the bridge to die. “It was a popular place to picnic under just to be there when somebody would jump,” Sabelzski said. Witnessing death as a spectacle may seem morbid to the average person today, but the turn of the 20th century was still a time of public executions, he said.

The Gilded Age in America mirrored the Victorian era in Europe; not only were people dying at higher rates than they are today, but there was also a preoccupation with death. Newspaper articles often framed High Bridge suicides as fantastical and sensational. Postcards were even printed with an image of the bridge and the words “Suicide Bridge. Lincoln Park. Chicago.”

Behind the blunt news reports is a deeper story of hardship and despair.

No safety nets

The World’s Fair may have put Chicago on the map in 1893, but Durica said it was also a difficult year for the U.S. overall.

“The United States economy more or less collapsed,” he said. “It was the worst economic crisis prior to the Great Depression. Some economists believe that when this crisis was at its height, about a quarter of Americans were out of work.”

This economic downturn lasted the entire decade. Businesses were losing money, cutting wages and laying people off. There was no welfare or pension system.

“When we think about 19th-century suicides, we tend to think about, like, the Romantic poets with the capital R, and these young people who perhaps have been jilted in love and have no other option,” Durica said. However, many cases of death at the time were middle-aged people who couldn’t find work or who had debilitating ailments and didn’t want to burden their families.

In one story from the Chicago Daily Tribune in 1902, a man reportedly jumped in the lagoon, leaving a note behind in his coat pocket that read, “No friends, no money, no work; better to die.”

A few women attempted suicide at the bridge, but not necessarily because of financial hardship; often it was due to the prevalence of domestic violence in the 19th and 20th centuries.

According to the Chicago Inter Ocean newspaper in 1899, police found a woman named Ida Washburn near the High Bridge with her two young sons. Officers stopped her before she could jump. She told them her husband was abusive and this was her way of escaping. She had visible scars on her face. Nonetheless, police allowed her husband to take the family back home.

“If a husband wanted to use physical abuse against his wife or his children, it really wasn’t perceived as a problem,” Durica said.

There was not much institutional support for many of the social problems of the time. After the rash of suicides in the late 1890s, city officials considered installing a safety net under the bridge.

“But what is certainly missing in the 1890s is any kind of social safety net that might prevent people from wanting to even consider taking their lives in the first place,” Durica said.

Remembering what’s been forgotten

Police officers were eventually assigned to patrol the area, but they couldn’t stop everyone, according to Sabelzski.

In 1919, city officials decided to close the bridge. By the end of that year, Lincoln Park commissioners voted to dismantle the High Bridge entirely.

Today, rowers cruise down the lagoon past the grassy lawn and well-trodden trails where the High Bridge once stood. There’s no sign it ever existed.

“Wouldn’t it be great if there could be some sort of memorial to all the Chicagoans who decided to end their lives there?” Durica said.

Given all the hardships during the era of the High Bridge, he thinks the people who died there deserve to be remembered.

Erin Allen hosts and reports for WBEZ’s Curious City.