The Obama Presidential Center has spent a decade on the drawing board and under construction — two years longer than its namesake’s time in the White House.

But now the team of workers, erectors, fabricators and artisans are months away from completing the $800 million center that’s expected to open next spring.

I toured the site with one of its two lead architects, Billie Tsien, of New York-based Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects.

My full critique of the complex will have to wait until the project is done. But enough work has been completed to get a solid look at what will be the most expensive presidential center in U.S. history. Construction costs come to $620 million. The current leader, the George W. Bush Presidential Library, cost $327 million to build, according to the Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts.

More importantly, enough has been built to get a sense of what the public will get for giving up 20 acres of historic Jackson Park for a campus of new buildings, gardens, parkland — and the much-discussed 225-foot museum tower.

“What we did realize is that in 50 years, when none of us are here, people will want to pay homage [to Obama’s presidency],” Tsien said. “And I think that they’ll want to feel like this was an important time; that this was an important man. This was a crucial time in the history of our country. Therefore, the building needs to have a kind of power to it.”

‘I didn’t want to mess up an Olmsted park’

The presidential center is still an active construction site, with the hurly-burly of trucks and construction equipment entering and leaving the area. Much of the campus is blocked from public view by construction fencing along Stony Island Avenue.

Announced in 2015, the center was supposed to open in 2021. But lawsuits and federal reviews — triggered when the Obama Foundation decided to build the center in National Register-listed Jackson Park, designed by landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted — contributed to the delays.

Behind the fencing is a four-building complex: the museum tower, an auditorium, a Chicago Public Library branch and an athletic facility designed by the architecture firm Moody Nolan that’s located on the south end of the campus, near 63rd Street.

Much of the new parkland and topography is designed by New York landscape architects Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates.

Van Valkenburgh designed Maggie Daley Park. Tsien and Tod Williams are the architects behind the Logan Center for the Arts, 915 E. 60th St., on the University of Chicago campus.

“I live near an Olmsted park,” Van Valkenburgh said. “I’m an Olmsted lover … I did not want to mess up an Olmsted park.”

Van Valkenburgh created an active park space with winding paths, green areas and play areas. The hilly topography rises high enough to cover the roof of the center’s auditorium, public library and a partially-sunken 437-car garage, which are all south of the museum tower.

Portions of the raised landscape are as high as two stories, providing views of Woodlawn to the west and the Jackson Park lagoon and Wooded Isle to the east.

“The land kind of rolls up and absorbs,” Van Valkenburgh said. “It obviously doesn’t absorb the tower but [it makes the other buildings] not visible from Jackson Park. You don’t feel like there’s a parking structure there. You feel like there’s park landscape that’s for you, that’s public, that you’re sort of welcomed in to.”

A community vegetable garden, sledding hills and wide lawns for public gatherings and events are also being built.

The project also replaced a half mile of Cornell Drive, between Midway Plaisance and Hayes Drive, with parkland and a promenade.

With Cornell gone, park visitors can walk right up to the western bank of the lagoon without crossing six lanes of traffic.

Van Valkenburgh said the six-lane thoroughfare was lined with trees that were attacked by the ash borer insect.

“So we not only had a piece of parkland that was cut off from the rest of the park, we had a piece of parkland whose vegetation was going to go through radical decline because of this boring insect, which is wiping out ash trees,” Van Valkenburgh said.

“That helped us inch towards the sensibleness of using this site the way we did — get rid of Cornell and create parkland that is physically integrated with the rest of the park.”

North of the tower, where Midway Plaisance meets Jackson Park, Van Valkenburgh is recreating the Women’s Garden, an area that was ripped away in 2021 to make room for the presidential center.

The loss was particularly acute: The garden had been a tranquil, sunken space of shady trees and prairie stone garden walls designed in 1937 by May McAdams, the Chicago Park District’s first woman landscape architect.

Landscape architect Matthew Bird, principal at Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, said the new Women’s Garden will emulate some of the planting and circular forms that were found in the old space, while reusing McAdams’s prairie stone.

But the new space will be designed to collect all the stormwater that falls on the presidential center site and slowly release it into the adjacent Jackson Park lagoon “rather than discharging to city sewers, which are already overwhelmed,” Bird said.

Tower is about ‘ascendance’

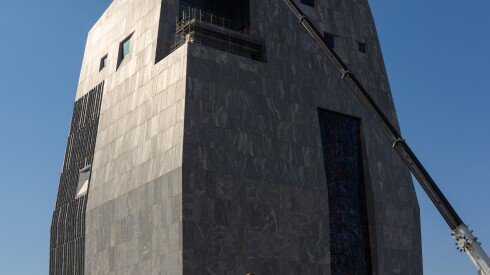

The one feature that has everyone talking is the museum tower, a nearly windowless building clad in a swirling, New Hampshire-mined granite called “tapestry.”

Earlier this year, I wrote the unfinished tower “seems much too big and husky for its park setting. And in its unfinished state, the building looks funereal enough to fit in at another historic South Side greensward: 183-acre Oak Woods Cemetery at 67th and Cottage Grove.”

Have time and the chance to see the interior changed my opinion? I won’t know until I see the finished tower inside and out.

But the interior spaces I saw, unfinished as they are, helped explain the building’s shape and size. Despite its height, the tower only has four stories because exhibition spaces have very high ceilings.

And artist Julie Mehretu‘s 83-foot by 25-foot stained glass window, called Uprising of the Sun, on the building’s north side promises to colorfully illuminate the ride on a nearby bank of escalators.

The windows in the Nelson Mandela Skyroom on the top floor boast quite impressive views south and west. You can’t see forever, but on a clear day, you can see the Chicago Skyway’s steel truss bridge over the Calumet River on the far Southeast Side.

Next month, the outside of the windows will carry words from former President Barack Obama’s 2015 speech honoring the 50th anniversary of Civil Rights marchers meeting violence — but making history — as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama.

The concrete letters are about five feet tall.

“When you’re in the top skyroom space, the idea is that you’ll be looking through the screen of Obama’s words,” Tsien said. “It’s kind of like you’re inside his head.”

But why, oh, why, build a skyscraper in an historic park — and then make it almost window-free?

“Well, there’s a reason — a practical one — which is a museum does not want any natural light in it,” Tsien said.

I had to ask: If there’s a functional need for a building with no windows, why put that function in a tower? Why not put it in some of the lower buildings beneath Van Valkenburgh’s parkland?

Tsien said the tower’s height helps the museum tell Obama’s story.

“The whole idea, when you see the exhibits, is about a kind of ascendance and moving through time,” she said. “So the idea is that you ascend through this time of his presidency, and you [get to the top], and you’re looking at the city.”