The first reference to insulin in a Chicago newspaper was both late and maddeningly provincial.

The Chicago Daily News debuted the name of the life-saving hormone that regulates blood sugar on the Feb. 13, 1923 editorial pages, in this embarrassing piece of whimsy mentioning the city’s king of electricity and rapid transit:

“To quiet a tormenting doubt whether insulin, the new diabetes cure, was or was not named in honor of Samuel Insull, we asked a doctor about it. He tells us that insulin was named from the so-called island of the pancreas. What a delightfully-romantic ring there is to the islands of the pancreas! One might almost do a ballad about them: ‘Twas off the pancreatic isles/I smoked my last cigar.”

The Daily News, perhaps significantly, was studded with advertising for quack diabetes remedies like Warner’s Diabetes Cure, mineral baths in Texas promising relief, and Sulferlick Mineral Water for those who couldn’t make the trip.

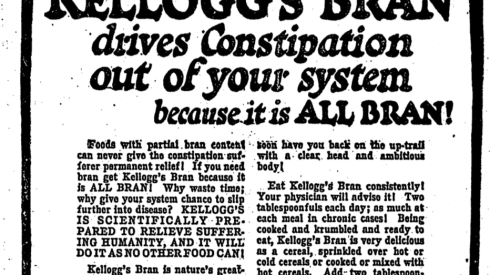

Kellogg’s Bran continually ran ads mimicking news articles, promoting itself as a “constipation corrective,” pointing out that “90 percent of all illness can be traced to constipation! It is responsible for most cases of diabetes….”

The Chicago Tribune at least shared the reason why the Daily News was waxing poetic on the subject: Drs. Frederick Banting and John McLeod were in town to talk to the City Club about their 1921 discovery, which, in May 1923, the Daily News finally got around to explaining in detail.

I mention all this because quackery is on the rise again, and because Friday, Nov. 14 is World Diabetes Day, the date chosen to coincide with Banting’s birthday. In 1923, an estimated 1% of the American population had diabetes. Now about 10% of adults do, with a third pre-diabetic.

Diabetes is divided in Type I and Type II. The latter amounts to 90% of cases, is where a body can’t use insulin produced by the pancreas to process sugar in the blood. It’s caused mainly by obesity, with help from genetics, and can be controlled by lifestyle changes and drugs like Metformin. Type I, also known as juvenile diabetes since it often presents itself in children, is when the pancreas no longer makes insulin, and it must be injected.

Regular readers know I contracted Type I a year ago — through some undetermined autoimmune disease. Diabetes is not bad, as far as chronic conditions go — no surgery, no radiation, you don’t have to die early, necessarily, if you do what you’re supposed to do. In my case that means swallow four pills a day, inject long-acting insulin every night, and short-acting insulin as need be, should I decide to, say, eat pizza or sushi or some other high carbohydrate food.

What have I learned from a year of diabetes? The biggest challenge is riding herd on prescriptions. Make friends with your pharmacist. To take insulin, you use an injector pen, which requires disposable needles. A 100-count box of 4 mm, 32 G needles costs about $54 with prescription at Walgreens [CVS wanted to charge over $200]. The pharmacist at Walgreens pointed out that I could buy a box, without prescription, for far less. You can get a box on Amazon for $10. They work fine.

A program I know stresses gratitude, and while I can’t honestly say I’m grateful to have diabetes, I can say that, compared to other ailments that have scythed through friends — cancer, heart failure, lung disease — diabetes is a walk in the park, if you make the effort manage it. I would not have picked diabetes, but diabetes picked me, and I’m rolling with it.

The real problem with diabetes is for people who aren’t obsessives enfolded in gold-plated health insurance. Millions of Americans have diabetes and don’t know it, or do know and don’t care, simply ignoring the problem. That’s a bad idea. Untreated diabetes can lead to blindness, loss of limbs, heart and kidney disease. My grandfather, who proudly never saw a doctor in his life, died of diabetes, age 63.

We’ve seen the inclination of Americans to ignore realities that demand difficult fixes — think global warming — so it should be no surprise that people do the same on a personal level, even with their own lives at risk.

Six years ago, I was having dinner in Buenos Aires, and mentioned to the bartender I had just been to a tango club, El Beso, “the kiss.”

“But did you dance?” she asked.

No, I explained, I didn’t know how to tango.

“You have to try it,” she insisted. “The life is only once.”

I think about that advice a lot. “The life is only once.” Short enough as it is. Don’t let diabetes shorten it further.