Since I was a teenager, the writer in me has felt a pull in two directions. The practical, realistic piece of me that’s dead-set on uncovering important stories and informing the public rages against the head-in-the-clouds, nose-in-a-book version of me that gets lost in a fictional world any chance I get.

This year, these two warring selves collided, resulting in a story in the Sun-Times that has proven to be one of the most memorable of my career.

It all started when seven of my cousins and I started a book club, religiously hopping on a video call from four different states once a month to discuss our latest read.

When it was my turn to pick a book, I agonized over the decision. We’re a family of harsh critics.

I landed on “The Great Believers” by Rebecca Makkai. It follows Yale Tishman and his group of friends through the AIDS epidemic in Chicago in the 1990s and explores the complications of messy relationships, generational trauma, creating family out of a ragtag group of friends and facing your own mortality.

Along with most of my cousins, I was enamored by the book. We had a lively discussion about the interpersonal dynamics, how Makkai’s writing made us feel — there were tears across the board — and the sticky moral questions of how people should act when they’re grieving.

I quickly launched into an obsession, learning everything I could about the AIDS crisis in Chicago. I listened to podcasts, watched documentaries and brought it up incessantly among my friends. I recommended the novel to anyone who would listen.

I read the author’s note several times and became even more impressed with not only the masterful writing and character building, but with the intensive reporting. Makkai busted out some serious journalism chops to produce the most historically accurate novel she could. I respected that — and it made me wonder if there was more reporting to be done by yours truly.

One of the elements of the novel that I learned wasn’t fictionalized was Unit 371, the AIDS floor at Illinois Masonic Medical Center. The way Makkai wrote about it, the unit seemed like a quintessential part of the fabric of 1980s Boystown, a hospital ward turned church, bar and everything in between.

I talked for hours with the founders of Unit 371, Drs. David Blatt and David Moore, former patients on the ward and AIDS activists. As gay men themselves, Blatt and Moore became mentors, brothers, role models and caretakers in the purest sense of the word.

Being at the forefront of the AIDS epidemic put a spotlight on these two doctors, who blend their tender humanity and complete commitment to defeating disease and saving lives.

They approached their patients as whole people, comforting them as if they were close friends. And some actually were close friends, to whom Blatt and Moore delivered bad news and saw die on the unit.

One of best aspects of my job is that I get to see the most gritty parts of humanity up close. Every day, I peer into a microscope to dissect a snapshot of someone’s life, and I see so much of the world represented in them. I see pain, I see heartache. I see laughter and triumph. I see the kind of losses that put a lump in your throat even years later.

The story about Unit 371 was one of those diamond-in-the-rough pieces that touches on what it means to be human — all the messiness, all the complexity, all the soul-crushing pain and heartening moments of connection and joy.

One paragraph about Blatt and Moore, who are a couple, emulates this perfectly: “It was [on Unit 371] they kissed the foreheads of patients after giving bad news, comforted grieving family and friends, celebrated their wedding with a cake homemade by one of the unit’s nurses, pushed beds together so infected lovers could be closer and sobbed behind closed doors in their offices when it all became too much.”

That’s what it means to be human.

I didn’t break any news with this story. I didn’t reveal anything astounding or change a law or break the internet. But I would hope that anyone who read that story felt something deep and powerful, unearthed a connection to someone different from themselves and understood a little bit more about why our past matters.

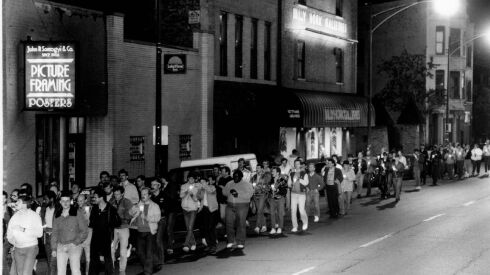

The story was connected to President Donald Trump’s moves to ax health care funding and cut dollars toward AIDS research, but much of the story focused on the past. The height of the epidemic hit Chicago in 1995, 30 years ago. There’s so much to be learned from confronting our history, seeking answers about how and why we ended up where we are today.

I wasn’t yet born when AIDS ravaged communities around the country, yanking the potential of a future from many young gay men and stealing older role models from a generation of queer youth. To me, and others who don’t remember those days, AIDS may have seemed like something far away and abstract. But the anxiety in Blatt and Moore’s voices when they discussed their fears surrounding funding cuts to AIDS research told me all I needed to know.

We aren’t that far from being back there, and just because the caseloads eventually diminished and medicine advanced to a level where it can keep HIV undetectable, doesn’t mean its impact, the massive hole where thousands of full lives should be, isn’t still felt and noticed. It will be felt forever.

When I decided to pursue journalism before fiction writing, I said it was because I realized the fictional characters and stories I had been so invested in as a young reader weren’t the only ones begging to be told. There were stories and characters in real life that were just as captivating, just as heart-wrenching and just as real. I wanted to find those stories and write them.

I thought of all the storybook characters I knew so intimately, all the ones who held my heart in their hands, some holding it gently and keeping it safe, others squeezing so hard it hurt, others leaving this earth and taking a piece of my heart with them. I thought of the people in my life who had done the same.

That’s what happened when I read the story of Yale Tishman and his friends — so I decided to find his real-life counterparts. Thank God I did.